Inshore Fisheries Research Section

Fecundity Work

Reproductive Biology

The reproductive biology of a species is among the most important life-history parameters that researchers must establish. Otherwise, the status of the stock cannot be accurately assessed and resource managers cannot develop an effective management plan for the fishery.

As would be expected, many species of fish exhibit distinct reproductive dynamics in different portions of their range. This is because fish reproduction can be affected by environmental variables such as temperature and salinity regimes. Therefore, the reproductive biology of a species must be investigated on a regional basis.

Several parameters must be known before we can establish the reproductive dynamics for each of our target species. We gather data in the field and in the laboratory to investigate size at maturity for both males and females, age at maturity for males and females, spawning periodicity and locations, and reproductive potential or fecundity.

Reproductive Biology Parameters

In order to establish some of these parameters, we obtain length data and make observations on maturity stages in the laboratory. To do this, we rely on a two-step process:

- gonads (ovaries or testes) are examined whole in the laboratory and an assessment is made based on established criteria for each species,

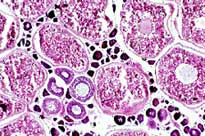

- a small section of the posterior portion of the gonad is preserved for microscopic examination. While macroscopic observations are useful, only microscopic examination can reveal certain characteristics that allow us to make accurate assessments of maturity stages. For instance, only in this manner can we gather conclusive evidence that the fish has spawned before and get an indication of how long ago it spawned.

Spawning Locations

So far, we have been able to determine a few spawning locations for spotted seatrout, black drum, and red drum in coastal South Carolina. We have accomplished this by conducting hydrophone (underwater listening) surveys in areas where these fish are likely to spawn. Being members of the drum family, Sciaenidae, spotted seatrout, black drum, and red drum produce drumming sounds during spawning events that can easily be detected using hydrophone equipment. We found spotted seatrout spawning aggregations in a few locations inside Charleston Harbor. Spawning red drum were heard in a deep hole located in the main channel leading to Charleston Harbor and in two slightly shallower areas off Morgan Island at the mouth of the Coosaw River in St. Helena Sound. We intend to expand our hydrophone survey areas in an effort to establish additional spawning locations for red drum in coastal South Carolina.

So far, we have been able to determine a few spawning locations for spotted seatrout, black drum, and red drum in coastal South Carolina. We have accomplished this by conducting hydrophone (underwater listening) surveys in areas where these fish are likely to spawn. Being members of the drum family, Sciaenidae, spotted seatrout, black drum, and red drum produce drumming sounds during spawning events that can easily be detected using hydrophone equipment. We found spotted seatrout spawning aggregations in a few locations inside Charleston Harbor. Spawning red drum were heard in a deep hole located in the main channel leading to Charleston Harbor and in two slightly shallower areas off Morgan Island at the mouth of the Coosaw River in St. Helena Sound. We intend to expand our hydrophone survey areas in an effort to establish additional spawning locations for red drum in coastal South Carolina.

Fecundity and Spawning Frequency

Currently, we are conducting research to estimate spawning dynamics for spotted seatrout. We are also investigating the fecundity of striped mullet. These two species differ in their reproductive behavior in that seatrout spawn repeatedly during the spawning season whereas mullet are thought to spawn only once per season.

We conduct field sampling to obtain female trout that are ready to spawn. Spawning occurs every evening throughout the season (April - September). Fish that are captured a few hours prior to spawning are sacrificed and their ovaries preserved for subsequent egg counts. We time the capture of pre-spawners so as to maximize the chances that we will count only those eggs that would have been shed that evening. In this way, we can estimate how many eggs a female trout produces per spawn, i.e. the batch fecundity.

To determine the spawning frequency; that is, how many times a female seatrout spawns per season, we turn to microscopic histological data. By examining histological sections of ovaries, we can establish whether a fish spawned before and approximately how long ago it spawned.

Once we know the number of eggs produced per batch spawn and the number of times a female spawns during the season, we can arrive at the total number of eggs that a female trout produces for the entire season, or its annual fecundity.

Preliminary data suggest that batch fecundity, spawning frequency, and annual fecundity may vary considerably according to age. Thus we are focusing our efforts into obtaining a large enough set of data to enable us to estimate batch fecundity, spawning frequency, and annual fecundity for every age class.

We use a similar protocol for estimating the fecundity of striped mullet. However, mullet are not known to be repeat spawners; they release all their eggs during a single spawning event. Furthermore, spawning only occurs offshore. Consequently, we have to use animals that are still developing towards a spawn to conduct our egg counts. This is not a problem because mullet eggs develop at the same rate and are all the same size (since seatrout are batch spawners, their eggs grow at different rates and different egg sizes may be encountered within an individual fish which can pose difficulties for counting).

The reproductive biology of striped mullet in this area is poorly known. Since our study began in 1997, we have been challenged by aspects of their reproduction that we are eager to elucidate. Cooperative research with other South Atlantic states (North Carolina, Georgia and Florida) is proving extremely beneficial.