Identifying Unique Cobia Populations through Genetics

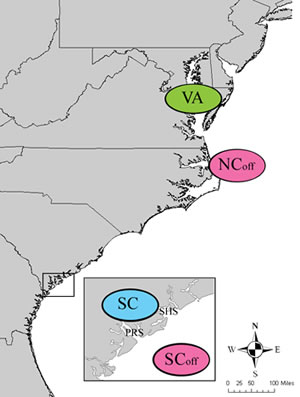

Cobia are a large popular sport fish capable of making long distance seasonal migrations and with a range that includes most of the world’s tropical and subtropical waters. In the spring and early summer months, cobia along the southeastern United States are thought to migrate with warming waters from Florida to the Chesapeake Bay. During the spring and summer, large numbers of cobia enter high salinity bays and estuaries, including Port Royal Sound (PRS, fig. 1)) and St. Helena Sound (SHS) in South Carolina (SC), Pamlico Sound in North Carolina (NC), and the Chesapeake Bay. The nature of these inshore migrations was thought to be for either feeding or reproduction and only recently have SCDNR biologists determined that spawning was occurring in SC estuaries. Evidence that these estuaries are used as spawning grounds raised important questions about the genetic structure and management of cobia in SC.

It is expected that migratory fish, like cobia, with a worldwide distribution and long distance migratory patterns would be unlikely to be separated into small unique populations, but rather be one large population (for example, the US Atlantic Coast). However, if these fish are returning to the same estuary every year to spawn, the potential to have small unique populations increases within such estuaries. Small unique populations are often more vulnerable to overfishing, habitat reduction, and effects of pollution because once the populations are severely impacted, there are no new fish coming back to sustain the population. Because cobia are using PRS and SHS for spawning purposes, evaluating the levels of genetic structure between these known inshore spawning aggregations and fish captured outside of known spawning habitat is very important.

In order to determine if the cobia captured in the different estuaries along the US southeast coast are part of smaller unique populations or part of one large coastal population, SC researchers at SCDNR’s Marine Resources Research Institute developed genetic techniques that are used to determine differences between groups of fish and even identify individual fish in the wild by their DNA. These genetic tools were first developed to identify hatchery-produced fish that have been released by SCDNR’s cobia stock enhancement research program.

Small pieces of tissue taken from the fishes’ fins (fin clips) were collected from cobia at fishing tournaments, as well as from fish carcasses provided by cooperating anglers and SCDNR personnel during the late spring and summer months of 2008-2011 (April-July). Samples were also collected in Virginia (VA), NC, SC, and Georgia (GA). Anglers were asked to provide information about the donated samples, including location of capture (inshore versus offshore).

Our genetic analysis showed that all fish captured offshore, throughout the southeast US Atlantic coast, were similar to one another, suggesting one big spawning population with lots of mixing. However, fish sampled within PRS were genetically different from fish sampled in offshore waters. We saw similar results from fish sampled within Chesapeake Bay; they were genetically different than both fish captured within PRS and in offshore waters (Fig. 2). These results suggest that during cobia’s annual migrations, the same individuals are returning to the same inshore aggregations to spawn

These results are complemented by recapture data collected by SCDNR’s cobia stock enhancement research program. Experimental stocking of cobia produced at the Waddell Mariculture Center has occurred between 2004-2012. There are numerous examples of fish released in PRS being recaptured back in PRS in later years. The recapture of these stocked fish within their release estuary 1-3 years post-release suggests some degree of natal homing occurs within these inshore cobia aggregations, supporting the identification of their unique genetic population structure. Additionally, results from South Carolina’s marine game fish tagging program indicate that over 90% of tag recaptures from fish initially tagged within PRS occurred back in the sound or the immediate vicinity.

Based on the genetic information brought to light by this research in the southeastern Atlantic coast of the US, cobia populations are quite genetically diverse both overall and within localized areas. However, the detection of unique populations of cobia within this portion of their range has implications on the appropriate management unit(s) for this important recreational fishery. As with many aspects of cobia’s life history, the answer does not appear to be straightforward. For example, a recommendation based solely on information gathered from the offshore collections, which shows high levels of movement along the southeast US Atlantic coast, might include continuing the single population management strategy as overfishing in one offshore area would impact other areas as well. In contrast, a recommendation based solely on the inshore collections, which indicate the presence of distinct population segments and estuarine fidelity in cobia, might favor separate management of the population segments, as localized fishing pressure would primarily impact the local population. Considering the genetic uniqueness of the inshore aggregations, it is concerning that the majority of the fishing pressure on these aggregations targets the reproductive pool on their spawning grounds. However, perhaps given the complicated life history of cobia, a more appropriate recommendation would include a two-tiered strategy in which cobia are managed as a single umbrella population for offshore activities in conjunction with inshore aggregation-specific management options at the local level. Such a strategy would provide flexibility to fisheries managers challenged with promoting sustainability within a localized spawning aggregation.