Setting Cobia Stock Boundaries

Cobia, Rachycentron canadum, is a large pelagic fish found in tropical, subtropical and warm temperate waters worldwide, excluding the Eastern Pacific. In South Carolina, they are a highly-prized game fish that are available to anglers during annual spawning aggregations in St. Helena and Port Royal sounds from mid-April to mid-June. In federal waters, cobia are managed jointly by the South Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico Fisheries Management Councils. In January of 2012, Coastal Migratory Pelagics Amendment 18 was enacted, dividing US cobia into a South Atlantic stock and Gulf of Mexico stock, with the division occurring at the traditional management council boundary in the Florida Keys. Amendment 18 also provided an annual catch limit (ACL) for both stocks. The Southeastern Data Assessment and Review (SEDAR) stock assessment for cobia is currently underway, with the data workshop occurring in Charleston in February of 2012. As SCDNR has been heavily involved in cobia stock enhancement and life history research, a large contingency from the agency was on hand to participate in the process.

The first step in any stock assessment process is to determine what stock boundaries are appropriate for the species. Creating appropriate boundaries is essential to the stock assessment and management process, as different stocks may have different life history characteristics and fishing pressure can be highly variable throughout a species’ range. With Amendment 18 arbitrarily establishing the cobia stock boundary at the Monroe County line in the Florida Keys, we wanted to determine their true biological boundary based on scientific data. The Florida Keys serve as a biological barrier for many species and it has long been speculated that cobia migratory groups in both the South Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico mix along the Keys in winter. We evaluated both genetic and tag return data to determine if the proposed Council boundary is appropriate for cobia.

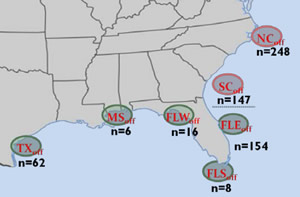

For the last six years, researchers at SCDNR's Marine Resources Research Institute have been collecting genetic samples in the form of fin clips from cobia throughout the U.S. Atlantic and Gulf waters and even from locations as distant as South Africa and Australia. While these non-lethal genetic samples were originally collected to look for the presence of hatchery-released fish in the local population, they can also be used to evaluate population structure throughout their range. If the Florida Keys serves as a barrier between Gulf and Atlantic populations, we would expect to see genetic differentiation between Gulf and Atlantic fish. Somewhat unexpectedly, based on cobia’s high potential for long distance movements, the genetic evaluation did detect a difference between the two populations, but that break did not occur in the Florida Keys. Fish collected on the southeast Florida coast (St. Lucie) were genetically similar to fish collected throughout the Keys and the Gulf, but were genetically distinct from fish collected from South Carolina to the north (fig. 1).

While the genetic work seemed to support the idea of a mixing zone/barrier around the Florida Keys, it created some new questions. While there are two genetic populations, pinpointing the boundary zone was a difficult task. According to the genetic work, that zone occurs somewhere between St. Lucie, Florida and Port Royal Sound, SC. Unfortunately, we didn’t have any genetic samples from this area to include in the analysis. Without genetic data, we had to turn to more traditional fisheries data sources, specifically tagging programs, to fill in the blanks.

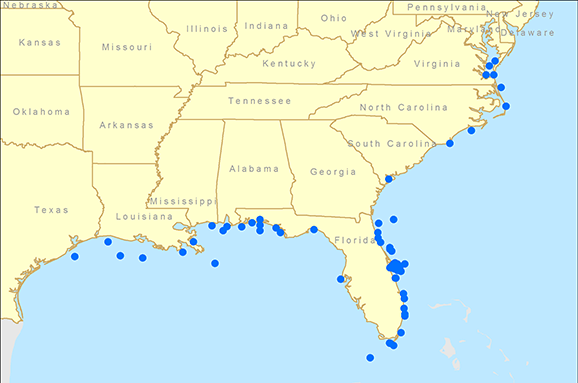

Fortunately, there were several long-term tagging datasets available to help us understand the movement patterns and population structure of cobia. Datasets from the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, SCDNR, NOAA’s Southeast Fisheries Science Center, Mote Marine Laboratory, and the Gulf Coast Research Laboratory were combined and evaluated by SCDNR staff to try and answer some of the questions that the genetic analyses raised. Specifically, we wanted to know if fish tagged along the east coast of Florida would be more likely to be recaptured to the north (in the Atlantic) or south (in the Gulf). The east coast of Florida was partitioned into three zones: Brevard County, north of Brevard County, and south of Brevard County. Brevard County was chosen as a reference point because it contains Cape Canaveral, a geographic feature that serves as a barrier for many other marine species.

The results of the tag data analysis agreed strongly with the genetic analysis. Fish tagged north of Florida were rarely captured in the Gulf (2%) and fish tagged in the Gulf were rarely captured north of Florida (1%). Fish tagged in Brevard County were mostly recaptured in Brevard County (30%) or the Gulf (46%) while only 10% were recaptured north of Brevard County (fig. 2). These data support the genetic analysis that fish captured along the southeast coast of Florida are part of a Gulf population and not the Atlantic population. Interestingly, none of the recaptures of fish tagged in the Florida Keys (n=182) occurred north of Brevard County, providing further evidence that any mixing zone/barrier occurs further to the north. While there is no real “line” that delineates a northern population from a southern one, the data suggest that the populations overlap somewhere around or to the north of Cape Canaveral, Florida. Additional genetic samples are currently being collected from these locations in order to more precisely understand cobia population dynamics. From a management perspective, these data were used to reject the long-held belief that Atlantic and Gulf populations mix along the Florida Keys. Instead, the current stock assessment places the stock boundary at the Florida/Georgia line, a move that could have significant impacts on the future management of the fishery. Our research further confirms the utility of collecting and analyzing data from both traditional fisheries techniques, such as game fish tagging programs, and from cutting-edge technology like population genetics.