Sea Turtles

Sea turtles are among the largest reptiles in the world and inhabit almost every ocean. Fossil evidence indicates sea turtles shared the Earth with dinosaurs over 210 million years ago. Sea turtles are cold-blooded, air breathing, egg laying reptiles that deposit their eggs on dry, sandy beaches. Sea turtles differ from freshwater turtles because they have flippers instead of feet, cannot retract their heads and spend all of their life in salt water, except when females come ashore to lay eggs. There are seven species of sea turtles in the world. They are the loggerhead, Kemp's ridley, green, leatherback, Australian flatback, hawksbill and olive ridley. The loggerhead, Kemp's ridley, green and leatherback sea turtles can be found in South Carolina's near shore waters April through November or nesting on our beaches from May through October. Loggerheads are the most common sea turtle found in our state's coastal waters and nesting on our beaches. Sea turtle nests and strandings in South Carolina can be followed in real time on the Sea Turtle Program web site: https://www.dnr.sc.gov/seaturtle/.

Life History

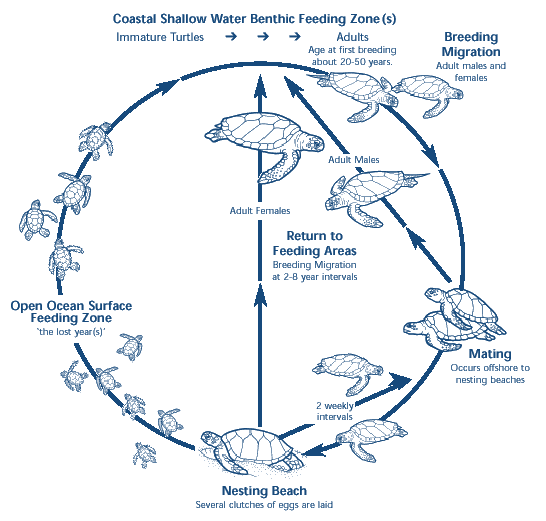

All sea turtles have a similar life history. Since loggerheads are the most common species found in South Carolina, the following life history information is specific to this species. The reproductive season begins when males and females mate in early spring. Females crawl onto the beach at night, 30 days after breeding, from May to August and deposit an average of 120 white, leathery eggs similar in appearance and size to a ping pong ball. They deposit these eggs in a nest cavity that is approximately 18 inches deep. The cavity is dug with their hind flippers in the dry sand above the high tide line. Each female will nest, on average, four times per season with two week intervals between each nesting event. The eggs incubate for approximately 60 days and during this time are susceptible to predation by raccoons, feral hogs, coyotes and ghost crabs. The temperature of the nest during the second trimester of incubation will determine the sex of the hatchlings. Hatchlings emerge from the nest at night and crawl towards the ocean using several cues, primarily celestial light reflecting off the ocean, to find their way.

Once they reach the ocean, they swim continuously for about 36 hours to escape predators that may prey on them in coastal waters. They swim offshore in search of large clumps of Sargassum seaweed where they are camouflaged while feeding on a variety of small invertebrates. During the next 10 – 12 years they lead a pelagic existence and float actively and passively in the North Atlantic Ocean gyre. Once they reach approximately 20 inches in shell length, they move back into coastal waters along the Continental Shelf and begin feeding on bottom prey such as crabs and mollusks. They spend the rest of their juvenile and adult lives in these Shelf waters.

Threats

Sea turtles face many natural and human-caused threats during all stages of their life cycle. The primary natural predator of juvenile and adult sea turtles is the shark. A significant threat is accidental capture in commercial fisheries. Long line fishing, gill nets and bottom trawling can result in the lethal capture of sea turtles.

The use of Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDs) by shrimpers has reduced the occurrence of sea turtle deaths. However, these species still face many challenges for survival. Collisions with boats, including propellers, are becoming a significant problem as coastal areas continue to develop. Artificial light visible from the beach is harmful because it disorients adults and hatchlings, causing them to wander away from the ocean. Disoriented hatchlings are more susceptible to nocturnal predators. Pollution can cause sea turtle mortality. For example, plastic bags may be mistaken as food and ingested, and sea turtles can become entangled in monofilament line. Beachfront development interferes with the natural erosion and accretion along dynamic barrier islands which results in the loss of nesting habitat. Climate change is a threat to sea turtles, especially when coupled with beachfront development. Rising oceans move dynamic beaches landward. When this occurs on developed beaches, nesting habitat is lost when sand cannot migrate landward because of infrastructure or when beaches are armored to protect property. Warming temperatures can also alter the natural ratio of male to female turtles that are produced in a nest.

Protection

All four species of sea turtles found in South Carolina are protected by state and federal law, principally by the US Endangered Species Act of 1973. Additionally, all species of sea turtles are protected by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). They are also listed as endangered or vulnerable by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Endemic Sea Turtles

Loggerheads

Loggerheads (Caretta caretta) are the most widespread and commonly found sea turtle that nests in the southeastern United States. They were designated as the official South Carolina state reptile in 1988. Loggerheads are named for their massive heads and powerful jaws that enable them to feed on hard-shelled prey, such as whelks, crustaceans and conch. Loggerhead turtles have an oval-shaped carapace that is dark reddish-brown while their flippers and lower plastron are light yellow. Adult loggerheads can weigh as much 300 pounds and reach up to four feet in shell length. Loggerhead nesting has been well documented and has averaged 3,378 nests per year over the last 10 years in South Carolina.

Kemp's ridleys

Kemp's ridleys (Lepidochelys kempii) are the smallest and rarest of the seven sea turtle species, weighing approximately 100 pounds and as adults, growing to two feet in shell length. Adults have a round grayish-black to olive carapace (which lightens in color as the turtle ages) that is as wide as it is long. They feed on fast swimming crabs, such as blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus). Kemp's ridleys nest primarily near Rancho Nuevo, Mexico. They do not typically nest in South Carolina but can be found in inshore and near shore waters from April through November. However, a Kemp's ridley nest was recorded on Litchfield by the Sea in 1992 and South Litchfield in 2008 (less than a mile from the 1992 nest site).

Green sea turtles

Green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) are the largest hard-shelled sea turtle species. Their common name is derived from the green fat, or calipee, in their body due to their herbivorous diet. They have a serrated jaw for tearing grass, weigh approximately 300 - 350 pounds as adults and average five feet in shell length. In September 1996, the first documented green turtle nest was laid on South Island in South Carolina. Since 1996, green nesting has become more frequent. Although green turtles do not typically nest in South Carolina, juvenile turtles consistently utilize South Carolina’s inshore and near shore waters as foraging grounds from April through November.

Leatherbacks

Leatherbacks (Dermochelys coriacea) are the largest and widest ranging sea turtles. These sea turtles are unique because they do not have a hard shell, but a leathery shell with distinct longitudinal ridges. Although cold blooded, they can maintain a body temperature warmer than ambient. They range from 800 - 1,300 pounds and reach six feet in shell length. Leatherbacks feed on jellyfish in South Carolina near shore waters in the spring and fall while migrating between Nova Scotia feeding grounds to tropical nesting beaches. In 1996, the first South Carolina record for a leatherback nest was documented on St. Phillip's Island. Since 1996, leatherback nesting has become more frequent.

Interesting Sea Turtle Facts

- Sea turtles are revered in many cultures. Around the world there are numerous indigenous tales and legends that depict turtles as guardians or creators of life on Earth. In Hawaii, the turtle is a symbol of good luck and a Hindu symbol depicts the world as resting on the back of a turtle.

- Leatherbacks dive deeper than any other turtle species with recorded dive depths of up to 4,000 feet. Given the pressure and temperature at this depth, this is a remarkable dive for any air breathing vertebrate.

- Loggerhead hatchlings born on the beaches of South Carolina, North Carolina, Florida and Georgia live the first years of their lives in the pelagic environment off the west coast of Africa.

- It takes loggerheads 25 - 30 years to mature and reproduce. You cannot age a turtle and no one knows exactly how long they live.

- About 100 species of animals and plants have been recorded living on one single loggerhead, making them an entire mobile, living, breathing ecosystem.

- The smallest sea turtle is the Kemp's ridley. The largest recorded leatherback was found stranded on the coast of Wales in 1988 and weighed roughly 2,020 pounds.

Sea Turtle Conservation and Ethics

Biologists urge the public to assist with sea turtle conservation by reporting all dead or injured sea turtles to 1-800-922-5431. Additionally, the following tips are useful:

- Never disturb a sea turtle crawling to or from the ocean.

- Once a sea turtle has begun nesting, observe her only from a distance.

- Do not shine lights on a sea turtle or take flash photography.

- Turn out all lights visible from the beach, dusk to dawn, from May through October.

- Turn off all outdoor and deck lighting to reduce disorientation for nesting adults and hatchlings.

- Close blinds and drapes on windows that face the beach or ocean.

- Fill in holes on the beach at the end of each day as adults and hatchlings can become trapped.

- Do not leave beach chairs, tents etc. on the beach overnight.

- Never attempt to ride a sea turtle.

This publication was made possible in part with funds from SCDNR Check-off for Wildlife funds, SCDNR endangered species license plate sales, US Fish and Wildlife Service and NOAA Fisheries Endangered Species Act Section 6 funding.

Suggested Reading

- Carr, Archie. So Excellent a Fishe. The Natural History Press, Garden City, New York. 1967.

- Carr, Archie. The Windward Road. University of Florida Press, Tallahassee Florida. Republished 1979.

- National Research Council. Decline of the Sea Turtles: Causes and Prevention. National Academy Press, Washington, DC. 1990.

- Safina, Carl. Voyage of the Turtle: In Pursuit of the Earth's Last Dinosaur. Henry Holt and Co., LLC, New York, New York. 2006.

Sea turtles in South Carolina

The above information on the sea turtle is available in a brochure, please download the Sea Science - Sea Turtle (PDF)

Author credentials: Marine Turtle Conservation Program of the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources.