Jellyfish

- Food

- Glossary

- Life Cycles

- Local Jellyfish

- Locomotion

- Prevention

- Treatment of Sting

- Saltwater Fishing Conservation & Ethics

- Venom Apparatus

Few marine creatures are as mysterious and intimidating as jellyfish. Though easily recognized, these animals are often misunderstood and feared by beach goers, even though most jellyfish in South Carolina waters are harmless. This publication will help coastal residents and vacationers learn which jellyfish to avoid, and the ones you can safely ignore.

Jellyfish belong to a large group of marine animals that include attaching organisms such as sea anemones, sea whips, corals and hydroids that grow attached to rocks or other hard surfaces. Jellyfish and their relatives such as the Portuguese man-of-war are mobile, either actively swimming or pushed by winds and currents.

Both stationary and mobile members of this group have radial symmetry with body parts radiating from a central axis. This allows jellyfish to detect and respond to food or danger from any direction.

Jellyfish have an outer layer which covers the external body surface, and an inner layer which lines the gut. In between is a layer of thick elastic jellylike substance called mesoglea or middle jelly.

Jellyfish have a simple digestive cavity with four to eight oral arms near the mouth. These arms transport food captured by the tentacles into the mouth.

Lacking a brain, jellyfish instead have a elementary nerve net capable of detecting light, odor and other stimuli and coordinating the animal’s responses.

Jellyfish exist in many sizes, shapes and colors. Most are somewhat transparent or glassy, with a bell shape. The bell may be less than an inch across or more than a foot across. A few species reach seven feet in diameter. The tentacles of some jellyfish grow to more than 100 feet long. Regardless of their size or shape, most jellyfish are very fragile, consisting mostly of water.

Jellyfish inhabit all the world's oceans and can withstand a wide range of temperatures and salinities. Most live in shallow coastal waters, but a few inhabit depths of 12,000 feet.

Life Cycles

Jellyfish have alternate generations in which the animal passes through two different body forms. They begin life as small polyps attached to solid surfaces such as rocks or shells. Using their tentacles, polyps feed on microscopic organisms in the water. Polyps can multiply by producing buds or cysts that separate from the first polyp and develop into new polyps.

When fully developed, polyps constrict in their bodies, eventually producing larvae which resemble a stack of saucers. Each individual saucer develops into a tiny jellyfish which separates itself from the stack and becomes free swimming. In a few weeks, they grow into an adult jellyfish, called a medusa.

The dominant and conspicuous medusa are either male or female. The reproductive organs (gonads) develop in the lining of the gut. During reproduction the male releases sperm into the water and the swimming sperm are swept into the female. Embryos develop either inside the female or in brood pouches along the oral arms.

Eventually, small swimming larvae leave the female and enter the water column. After several days they attach themselves to something firm on the sea floor gradually transforming into flower like polyps to start the life cycle over again. Jellyfish medusae normally live for a few months; however, the polyp stage may survive for years.

Locomotion

Adult jellyfish drift in the water with limited control over horizontal movement. However, muscles that contract the bell, reducing the space under it, force water out through the opening with pulsating rhythm that creates vertical movement.

Some jellyfish, such as the sea wasp, descend to deeper waters during the bright sun of the midday and surface during early morning, late afternoon and evening. For horizontal movement from place to place however, jellyfish largely depend upon ocean currents, tides and wind.

Food

Jellyfish form an important part of the marine food web. Carnivorous, they feed on a variety of small floating organisms as well as comb jellies and occasionally other jellyfish. Larger jellyfish can capture and devour large crustaceans and other marine organisms.

In turn, many marine animals, including spadefish, sunfish, and sea turtles eat jellyfish. Some species, including the mushroom and cannonball jellyfish, are considered a delicacy by humans. Pickled or semi-dried mushroom jellyfish are consumed in large quantities in Asia, where they constitute a multimillion-dollar part of the seafood business.

Venom Apparatus

For defense and feeding jellyfish have specialized stinging cells which contain venom. The stinging structure consists of a hollow coiled thread with barbs along its length. These nematocysts are concentrated on the tentacles or oral arms. A single tentacle can have hundreds or thousands of nematocysts embedded in the epidermis.

When tentacles make contact with an object, pressure within the nematocyst forces the stinging thread to rapidly uncoil. The thousands of nematocysts act as small harpoons, firing into prey and injecting paralyzing toxins.

Jellyfish use stings to paralyze or kill small fish and crustaceans, but the stings of some jellyfish can harm humans. Jellyfish do not “attack” humans, but swimmers and beachcombers can be stung when they accidentally touch jellyfish tentacles.

The severity of the sting depends on the species of jellyfish, the penetrating power of the nematocyst, the thickness of the victim’s skin, the sensitivity of the victim to the venom. The majority of stings from jellyfish occur in tropical and warm waters. Most jellyfish along the South Carolina coast inflict only mild stings that result in minor discomfort.

Local Jellyfish

Although most jellyfish that inhabit South Carolina waters are harmless to humans, there are a few that require caution. Learning how to identify the different species can help you decide which ones can be safely ignored.

Cannonball Jelly

(Stomolophus meleagris)

Cannonball jellyfish are the most common jellyfish in our area, and fortunately, one of the least venomous. During the summer and fall, large numbers of this species appear near the coast and in the mouths of estuaries. Cannonball jellies have round white bells bordered below by a brown or purple band. They have no tentacles, but they do have a firm, chunky feeding apparatus formed by the joining of the oral arms.

Cannonballs rarely grow larger than 8-10 inches in diameter. Commercial trawl fishermen consider them pests because they clog and damage nets, and slow down fishing.

Lion’s Mane

(Cyanea capillata)

Also known as the winter jelly, the lion’s mane typically appears during colder months. The bell, measuring 6-8 inches, is saucer-shaped with reddish-brown oral arms and eight clusters of tentacles hanging underneath. Stinging symptoms are similar to those of the moon jelly but, usually more intense. Pain is relatively mild and often described as burning rather than stinging.

Mushroom Jelly

(Rhopilema verrilli)

The mushroom jelly resembles the cannonball jelly, but differs in many ways. The larger mushroom jelly, growing 10-20 inches in diameter, lacks the brown band of the cannonball and is much flatter and softer. Like the cannonball, the mushroom jelly has no tentacles and a chunky feeding apparatus, but differs in its long fingerlike appendages that hang from the feeding apparatus.

This species is also considered a pest by commercial fishermen, but they are much less of a problem than cannonball jellies. The mushroom jelly does not represent a hazard to humans.

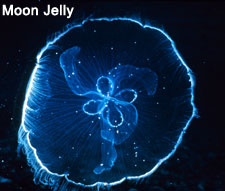

Southern Moon Jelly

(Aurelia marginalis)

Probably the most widely recognized jellyfish, the moon jelly occurs infrequently in South Carolina waters. It has a transparent, saucer-shaped bell and is easily identified by the four pink “horseshoes” visible through the bell. It typically reaches 6-8 inches in diameter, but some exceed 20 inches.

The moon jelly is only slightly venomous. Contact can produce prickly sensations to mild burning. Pain is usually restricted to immediate area of contact.

Sea Nettle

(Chrysaora quinquecirrha)

Common in the summer, this jellyfish is saucer-shaped, usually brown or red, and 6-8 inches in diameter. Four oral arms and long marginal tentacles hang from the bell and can extend several feet.

Considered moderate to severe, sea nettle stings are similar to those of the lion’s mane. This species causes most of the jellyfish stings that occur in South Carolina waters. Exercise caution if sea nettles are observed in the water, and do not swim if large numbers are present.

Sea Wasp

(Chiropsalmus quadrumanus)

Known as the box jelly because of its cube-shaped bell, the sea wasp is the most venomous jellyfish inhabiting our waters. Their potent sting can cause severe skin irritation and may require hospitalization. Sea wasps are strong, graceful swimmers reaching 5-6 inches in diameter and 4-6 inches in height. Several long tentacles hang from the four corners of the cube. A similar species, the four-tentacled Tamoya haplonema, also occurs in our waters.

Portuguese Man-of-War

(Physalia physalis)

Although closely related to jellyfish, the Portuguese man-ofwar is not a “true” jellyfish. These animals consist of a complex colony of individual members, including a float, modified feeding polyps and reproductive medusae.

They typically inhabit the tropics, subtropics and Gulf Stream. Propelled by wind and ocean currents, they sometimes drift into nearshore waters of South Carolina. Though they visit our coast only infrequently, swimmers should learn to identify these highly venomous creatures.

The gas-filled float of the man-of-war is purple-blue, up to 10 inches long. Under the float, tentacles equipped with thousands of stinging cells hang from the feeding polyps which extend as much as 30 to 60 feet.

The man-of-war can inflict extremely painful stings. Symptoms include severe shooting pain described as a shock-like sensation, and intense joint and muscle pain. Pain may be accompanied by headaches, shock, collapse, faintness, hysteria, chills, fever, nausea and vomiting.

Initial contact with a man-of-war may produce only a small number of stings. But trying to escape from the tentacles may greatly increase stings. Severe stings can occur even when the animal is beached or dead.

Another jellyfish, the smaller by-the-wind-sailor, also has a blue bladder and occasionally enters South Carolina coastal waters, but causes only a mild, tingling sting. Given the significant danger of the man-of-war, all jellyfish having a blue float should be considered dangerous.

Treatment of Sting

If stung by a jellyfish, the victim should carefully remove the tentacles that adhere to the skin by using sand, clothing, towels, seaweed or other available materials. As long as tentacles remain on the skin, they will continue to discharge venom.

A variety of substances may reduce the effects of jellyfish stings. Meat tenderizer, sugar, vinegar, plant juices and sodium bicarbonate have all been used with varying degrees of success. Applying any form of alcohol, or urine may increase the pain and cause severe skin reactions.

Victims of serious stings should get out of the water as soon as possible to avoid drowning. If swelling and pain from more serious stings persist, prompt medical attention should be sought. Recovery periods can vary from several minutes to several weeks.

Prevention

Care should be taken when swimming in areas where dangerous jellies are known to exist or when an abundance of jellies of any type is present. Keep in mind that tentacles of some species may trail a great distance from the body of the organism and should be given lots of room. Stings, resulting from remnants of damaged tentacles, can occur in waters after heavy storms. Rubber skin-diving suits offer protection against most contact.

Be careful when investigating jellyfish that have washed ashore. Although they may be dead, they may still be capable of inflicting stings. Remember to take precautions when removing tentacles after contact or additional stings may result.

Saltwater Fishing Conservation & Ethics

Ocean resources, once thought to be unlimited, have declined rapidly in recent decades, due in part to the overharvest of many commercial and recreational species of fish and shellfish.

To reduce overfishing, all anglers should practice wise conservation practices and adopt an ethical approach to fishing.

Size and catch limits, seasons and gear restrictions should be adhered to strictly. These regulations change from time to time as managers learn more about fish life histories and how to provide angling opportunities without depleting fish populations.

The challenge of catching, not killing, fish should provide anglers with the excitement and the reward of fishing. Undersized fish or fish over the limit should be released to ensure the future of fish populations.

More and more South Carolina fishermen now practice tag and release, which not only conserves resources but also provides information on growth and movement of fish.

Saltwater fishermen can further contribute to conservation by purchasing a Saltwater Recreational Fishing License, which is required to fish from a private boat or gather shellfish in South Carolina’s salt waters. Funds from the sale of licenses must be spent on programs that directly benefit saltwater fish, shellfish and fishermen.

Help ensure the outdoor enjoyment of future generations by strictly adhering to all rules, regulations, seasons, catch limits and size limits, and through the catch and release of saltwater game fish.

Glossary

- Coelenteron

- a simple digestive cavity, which acts as a gullet, stomach and intestine, with one opening for both the mouth and anus.

- Ephyra

- first stage that resembles the adult jellyfish

- Epidermis

- outer layer of the jellyfish

- Gastrodermis

- an inner layer which lines the gut

- Gonad

- reproductive organ

- Medusa

- adult form of the jellyfish

- Mesoglea

- middle jelly, or a layer of thick elastic jellylike substance

- Nematocyst

- A capsule inside the cnidoblast that contains a trigger and a stinging structure.

- Phylum Cnidaria

- a structurally simple marine group of both fixed and mobile animals: sea anemones, sea whips, corals and hydroids

- Radial symmetry

- a body plan where the body parts radiate from a central axis Planulae-small swimming larvae

- Scyphistoma

- flower-like polyps of the larval stage

This publication was made possible in part with funds from the sale of the South Carolina Saltwater Recreational Fishing License and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Sportfish Restoration Fund. The South Carolina Department of Natural Resources publishes an annual Rules and Regulations booklet that lists all saltwater fishing regulations. Have an enjoyable fishing trip by reading these requirements before you fish.

Author credentials: J. David Whitaker, Dr. Rachael King and David Knott, Marine Resources Division

The above information on the jellyfish is available in a brochure, please download the Sea Science - Jellyfish information pamphlet which is in the Adobe PDF file format. Adobe® Reader® is required to open the files and is available as a free download from the Adobe® Web site.